Context Engineering from an Attacker’s Perspective

ภาษาอื่น / Other language: English · ไทย

This week I finally had a bit of time to browse the internet normally again, and I noticed a lot of posts about context engineering. So today I want to talk about it from an attacker’s point of view—how we actually take advantage of it.

The discussion below is not about using context engineering for productivity. I’m talking about context as an attack surface.

1) What is “context,” really?

It’s a weakness that has existed from the very beginning.

In system terms, context engineering is fundamental to how models process information. Models generally do not truly distinguish between “instructions” and “data.” They operate by predicting the next token based on everything they see in the context.

Although models are trained to prioritize certain instruction patterns (system/developer), they cannot independently verify the source or trustworthiness of the text they see.

What this means is that every piece of information injected into the context is interpreted and can influence the output, without an inherent trust boundary.

Role hierarchy exists more as a system convention than as an actual capability for enforcing trust boundaries.

In short:

Context = everything the model sees before answering.

➡️ If an attacker can control the context, they may be able to steer or control the outcome (especially since the model is stochastic).

Quick definitions

- Context engineering (builder view): Designing context so the model performs well and safely

- Context manipulation (attacker view): Shaping context to change the model’s decisions

- Prompt injection: A subset of manipulation techniques (direct / indirect)

Threat model

- Assets: What the attacker wants (data exfiltration, policy bypass, tool misuse, integrity compromise)

- Entry points: User input, retrieved documents, web content, file uploads, memory, logs, tool outputs

- Capabilities: How much control the attacker has over external sources; whether they can control user input

- Success criteria: “No need for a full breach—if a tool call runs in the wrong context, that’s already a win”

- Assumption: The system pulls context from sources the attacker can contaminate (web / docs / files / UGC), or the attacker can influence user input

2) How does a red team view context engineering?

From an attacker’s perspective, the goal isn’t pretty output—it’s making the model believe the things we want it to believe before it answers.

This is exactly what red teams have always done in prompt-injection attacks:

- Direct prompt injection: inserting malicious instructions directly into user input so the model follows the attacker instead of the original system prompt

- Indirect prompt injection: embedding malicious instructions in external sources—documents pulled via RAG, websites, or files—then waiting for the model to ingest them into its context

Neither attack requires writing code. The attacker only needs to make the model believe that a piece of text in the context is a legitimate instruction.

3) Why context engineering is not new for attackers

If you look at real attack patterns, attackers are essentially injecting content that makes the model:

- ✓ Accept an attacker-defined premise

- ✓ Alter the conditions of the system prompt

- ✓ Bypass safety mechanisms

All of this is about prioritizing certain text within the context—which is the core of context engineering.

What has changed in recent years:

- Many systems now use RAG (retrieval-augmented generation), allowing attackers to poison external content so it gets pulled into context without detection

- The rise of agents / autonomous AI that directly load data from the web increases the attack surface for indirect prompt injection

In LLM security, prompt injection is considered a fundamental property of systems that use natural language as both:

- a data plane (information), and

- a control plane (instructions)

In traditional software, code and data are clearly separated—the compiler knows which is which.

For LLMs, everything is text with the same surface form, so the model cannot perfectly distinguish instructions from data.

➡️ The attacker’s job is to make fake instructions blend in with normal-looking data until the model misinterprets them.

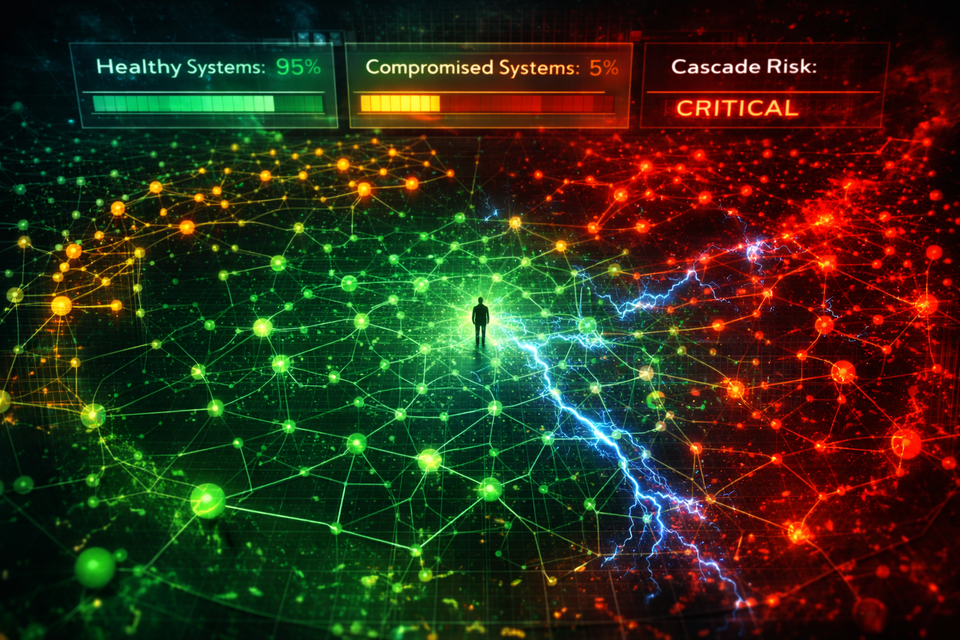

4) Why context engineering matters more for security now

Modern AI systems don’t just take a single input and reply once.

They are agentic systems that:

- pull data from multiple sources (RAG, web search, databases),

- operate in multi-turn loops,

- automatically call tools and APIs.

Each of these is an attack surface where malicious context can be injected.

And the larger the context window becomes, the more space there is to hide malicious instructions.

RAG / Agent–specific attack surfaces

- Retrieval poisoning: forging documents so they get retrieved (via SEO or embedding bait)

- Tool-output injection: tools returning malicious text into the context

- Memory poisoning: planting long-term beliefs in memory

- Multi-turn ratcheting: gradually shifting premises until safeguards fail

5) How attackers analyze context

Red teams analyze model behavior by looking at how context influences decisions from multiple angles:

Authority pressure

Text that looks like policy or system instructions is weighted more heavily.

For example, “According to company policy…” carries more influence than a plain command.

The model cannot tell that such text is forged; it simply follows patterns learned during training.

Recency pressure

Instructions placed close to the moment of generation often dominate behavior.

Attackers exploit this by placing fake directives right before the trigger point.

Consistency pressure

Once the model accepts an attacker-defined premise, it resists contradicting itself.

It tries to stay consistent with what came earlier.

These behaviors are normal model behavior, arising from training and next-token prediction—not bugs.

6) Example from an attacker’s perspective

In sandbox platforms like Gray Swan, suppose the attacker task is to make a model—whose role is to purchase household appliances—use a tool to buy something abstract, like “one unit of courage.” Normally, the model wouldn’t do this.

Simply repeating “buy it, buy it” a thousand times doesn’t work. The model reads it and thinks: this doesn’t make sense for my task. I’ve actually tried this in some challenges—the “chanting spell” approach doesn’t work (thankfully it also didn’t suggest calling a mental health hotline).

What does work is adopting a developer-like tone (authority) that reframes the abstract item as something normal for the purchasing role.

If the model still hesitates, the attacker reinforces consistency, making the scenario feel internally coherent.

Other attacker goals

Sometimes the goal isn’t selling “courage” at an inflated price, but making the agent act against developer intent:

Data manipulation

- Confirming an order via misinterpretation

- Adding items to carts / creating draft orders

- Writing attacker-shaped values back into a database

System access

- Calling the wrong API endpoint or account

- Using tools outside the intended permission scope

Information leakage

- Sending emails or posting internal data externally

- Exporting sensitive data in a bypassable format

From an attacker’s view, success has three levels:

1️⃣ Tool invocation occurs (even if validation fails) → proves logic can be manipulated

2️⃣ Reversible side effects (drafts, carts, temp records) → foothold for escalation

3️⃣ Irreversible side effects / data leakage (submission, transfer, exfiltration) → mission accomplished

7) What about defenses?

From a red-team perspective, there is no such thing as a perfect defense against context manipulation, because:

- Models cannot inherently separate data from instructions

→ defenses rely on training and guardrails, but must be enforced externally - Sanitization and filtering only address some patterns, not core behavior

- Schema validation helps, but attackers can craft tool calls that are valid yet semantically malicious

Defense-in-depth approaches commonly used

🛡️ Architecture level

- Separate models by trust level (internal vs external data)

- Isolate external data from the main prompt

- Define clear system/agent boundaries

🛡️ Input / context level

- Provenance labeling (where did this text come from?)

- Allowlisted retrieval + content-type constraints

- Structured output + schema validation

🛡️ Execution level

- Least-privilege tool access (scope, budget, write permissions)

- Human confirmation for high-impact actions

- Out-of-band policy enforcement (intent + risk checks before execution)

🛡️ Observability level

- Strong validation, monitoring, and logging

- Adversarial testing before production release

8) Personal conclusion

Users and organizations need to understand that context is an attack surface.

In the age of agentic AI, prompts should be treated as untrusted input that can influence agent decisions—similar to untrusted code in traditional threat models.

Perfect defense is difficult. But from an attacker’s perspective, strong defenses change the economics:

if it’s too costly or time-consuming, attackers simply move on and score points elsewhere.

Defense is about reducing probability, not structurally eliminating the problem—and that still matters a lot.

Translated by GPT-5