Looking at LLMs through a Finance Lens (2): VaR, Expected Shortfall, Stress Testing

ภาษาอื่น / Other language: English · ไทย

Tools born from “human fear,” not because the formulas are elegant

From the previous post, I introduced the idea that finance didn’t break because the models were wrong or not smart enough, but because what actually happened was something the models had never seen before.

In this post, I want to look at how finance has tried to live with that kind of fear through tools that have been used in practice for a long time: Value at Risk (VaR), Expected Shortfall (ES), stress testing, and simulation.

These tools didn’t arise from a desire to predict the future. They arose from a very basic human limitation: humans don’t fear averages — we fear bad days.

Humans don’t live their lives according to expected value.

Think about it: on a normal, uneventful day, you probably don’t remember much, right?

But you vividly remember days when everything went wrong — days when you lost a large amount of money, or made a decision you couldn’t undo.

Even if the average says “overall, it’s fine,” the human brain asks:

“Is there a day where I lose everything and can’t recover?”

The problem is that traditional statistical tools — mean, variance, standard deviation — were never designed to answer that question.

They answer questions that mathematicians like, but not the questions that executives, who must bear real consequences, actually ask.

That’s why finance had to create new tools.

Not because the old formulas were wrong, but because they didn’t align with human fear.

VaR (Value at Risk): speaking a language humans understand

When we talk about VaR, we usually see the 95% number. This isn’t sacred — it’s a psychological compromise.

- 100% → sounds like bragging

- 50% → feels like flipping a coin, too scary

- 95% → “this should be safe enough”

VaR was designed so a portfolio manager could say to their boss:

“On 95 out of 100 days, we shouldn’t lose more than X.”

Instead of saying:

“The portfolio’s standard deviation is 2.3%,”

which most people can’t really picture.

VaR is a language the human brain understands.

It’s not an explanation of the entire world.

Why VaR still isn’t enough

VaR solves part of human fear, but not the fear humans actually care about most.

Its key role is drawing a line:

“This is what we still call ‘normal.’”

Psychologically, VaR gives humans something they want — a boundary, a frame, and a number that says “most of the time, we survive.”

But real fear doesn’t stop at that boundary.

Humans aren’t afraid of crossing the line.

They’re afraid of what happens after crossing it.

VaR tells you:

“95% of outcomes won’t be worse than this.”

But it doesn’t tell you:

“How bad are the remaining 5% — and can I still move forward afterward?”

To make it concrete:

A portfolio that breaches VaR and loses 1 million, and one that breaches VaR and loses 10 million, are “equally risky” under VaR.

But to humans, they feel completely different.

This psychological gap is something VaR cannot close — and it’s why financial risk measurement never stopped at VaR.

Expected Shortfall: when humans ask about the point of no return

Expected Shortfall (ES) didn’t emerge because it’s mathematically prettier than VaR.

It emerged because humans asked a new question:

“If we’re truly unlucky, how bad does it get?”

ES acknowledges a hard truth: some events are rare, but when they happen, the game is over.

This isn’t about math elegance.

It’s about designing tools around fear of irrecoverable loss.

Stress testing and simulation: forcing ourselves to look at what we avoid

Even with VaR and ES, finance knows that humans tend to avoid thinking about frightening scenarios.

Stress testing isn’t prediction — it’s forcing ourselves to ask:

“If this terrible thing really happens, do we survive?”

Simulation serves a similar role. It’s not meant to cover every case, but to destroy false confidence.

These tools are psychological discipline, not crystal balls.

Bringing this fear into the LLM world

Humans worrying about bad days is normal.

When something new like LLMs enters the picture, we worry again.

The key difference is this:

In finance, the world itself isn’t adversarial. No one is optimizing day after day to deliberately make you collapse.

With LLMs, there are attackers — trying again and again, learning from failure, adapting. Personally, if I make no progress after two or three hours, I lose interest. But many red teamers are far more patient than that.

From the defender’s side, even if you simulate extensively, you’re still missing one thing:

what the attacker will try first.

More importantly, many failures in real LLM systems share a property: once executed, the damage is often irreversible.

Translating VaR / ES thinking into LLM systems

From a finance perspective, if we map the fear behind VaR and ES onto LLMs, it looks like this:

VaR and ES force humans to think about things they’d rather avoid.

VaR mindset for LLMs asks:

“In normal operation, what level of error can we tolerate while the system doesn’t break, the business keeps running, and no one has to explain themselves to executives?”

Examples:

- Minor factual errors

- Awkward tone

- Slightly inaccurate summaries

→ You review, double-check, fix it. Annoying, but acceptable.

This is noise you must live with — like daily market volatility.

ES mindset for LLMs asks a different question:

“If the worst day actually arrives — one system failure — what is the maximum damage, and can we live with it?”

For example:

Customer Support Bot

- Failure → nonsense answers

- Impact → customers annoyed

- Fixable → edit responses, apologize, adjust prompt

This is a VaR-type failure: frequent, tolerable.

Trading Copilot

- Failure → executes one wrong action

- Impact → money lost, legal issues, full audit trail

- Not fixable → damage already done

This is an ES-type failure: rare, but terrifying.

Two LLMs can have similar accuracy and benchmark scores, yet very different risk — because where they sit and what privileges they have are completely different.

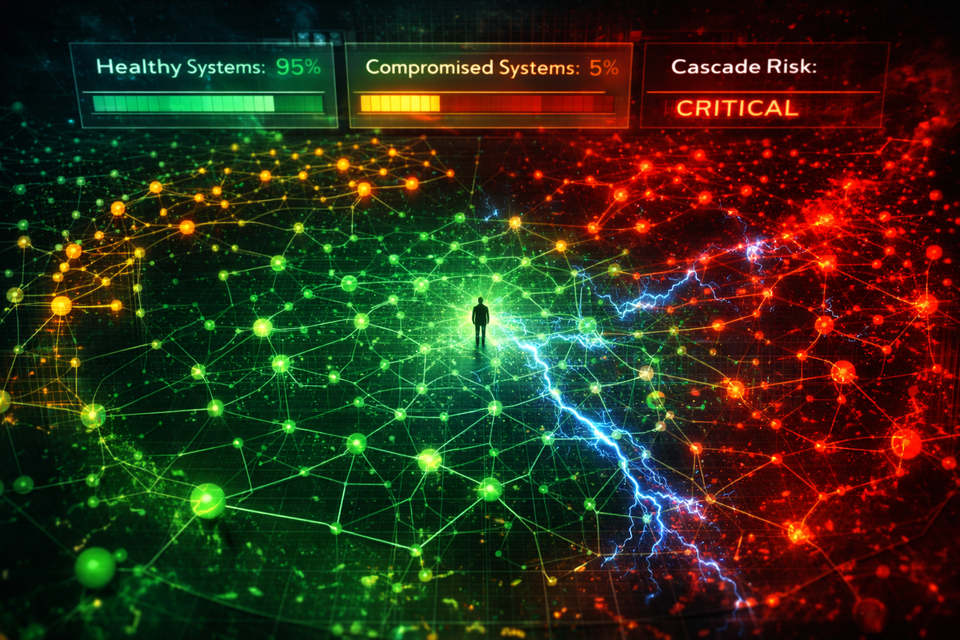

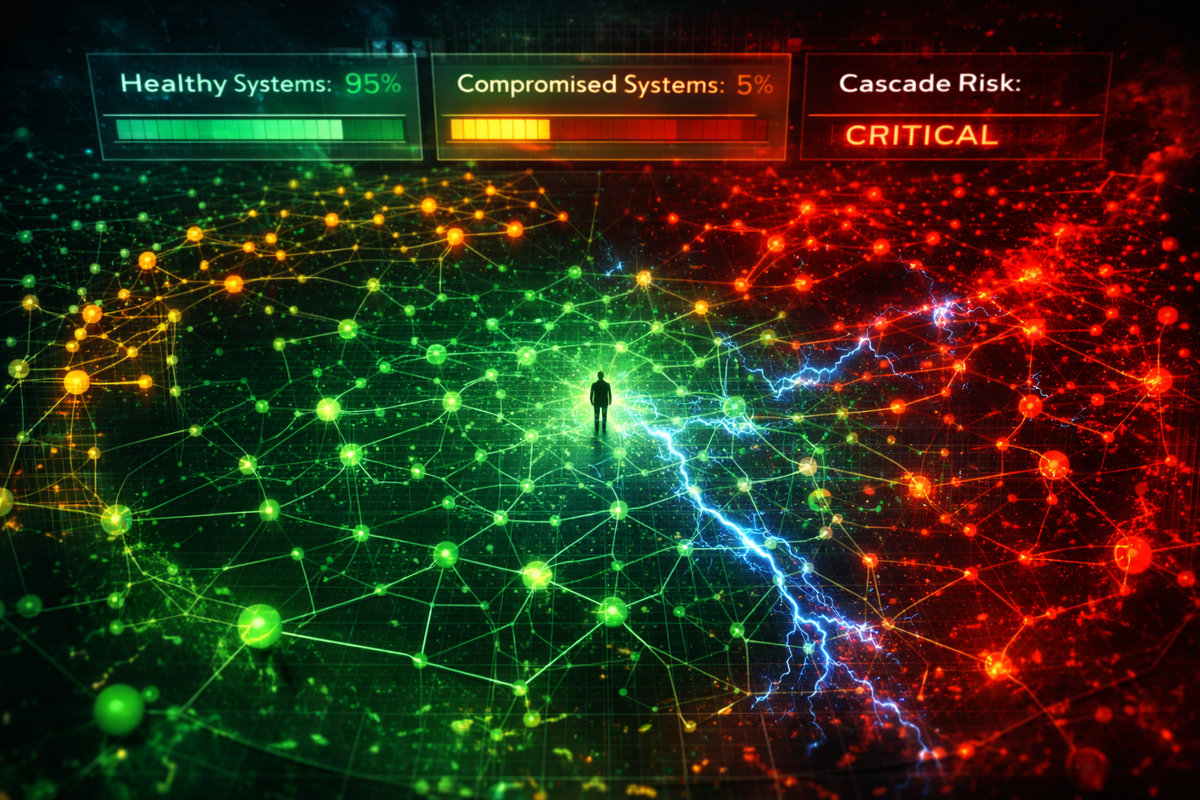

The crucial difference between finance and LLMs

In finance, VaR-type risks usually stay VaR-type. Daily volatility doesn’t instantly escalate into systemic collapse.

In LLM systems, that’s not true.

LLMs live in an adversarial world. An attacker can push a VaR-type risk into an ES-type risk.

A customer support bot that today just “sometimes answers badly”

Tomorrow might be jailbroken, tricked into pulling the wrong data, or leaking customer information.

Errors that used to be frequent, fixable, and mild

Can evolve into a one-shot catastrophe — with logs, evidence, and no rollback.

Internal Document Summarizer

- Failure → slightly inaccurate summary

- Impact → re-check original document (VaR-type: annoying but fine)

But what if the document contains hidden prompt injection?

- Attacker-driven → internal data leaks as part of the summary

- ES-type → irreversible data breach with full logs

That’s why applying a VaR / ES mindset to LLMs must always include an adversary assumption.

Not just:

“Is this VaR-type or ES-type?”

But also:

“Is someone actively trying to push it from VaR-type to ES-type?”

In the LLM world, the answer is almost always yes — especially if the system looks easy to manipulate.

This is why testing LLMs with ordinary benchmarks is like backtesting a portfolio only on calm market days. It tells you how the system behaves when everything is normal — not how badly it breaks when an attacker seriously tries.

Summary

VaR, ES, stress testing, and simulation didn’t arise because mathematics demanded them. They arose because humans needed tools that force us to look at the days we don’t want to imagine — and deal with irreversible fear.

Even if we can’t directly reuse the math, the mindset still applies. In both finance and LLM systems, the ones who suffer the consequences are humans.

LLMs aren’t just “smarter code.”

They are stochastic systems, with privilege, operating in the presence of adversaries.

The goal isn’t to invent formulas as fancy as finance’s.

It’s to remember to think about risk — the same way we never forget to think about financial risk.

In the next post, I’ll return to another classic lesson: what happens when the world goes out of distribution — and why “unlikely” events keep happening again and again.

English translation by ChatGPT (GPT-5.2), from the original Thai text.

This builds on Part 1 .